Thinking in Systems: Everything we know is a model

Understanding how systems work is invaluable, no matter what your goals are. Whether you want to create a better Marketing model or aspire to solve the global challenges that threaten our planet, Thinking in Systems is the place to start.

Marketers are responsible for building awareness, generating demand, and reporting actionable insights with accuracy and clarity. We try to fit all the moving pieces in simple linear models like funnels, but the reality is a lot more complex.

I was thrilled to find a book that provides a formal framework that can be applied to what we do and so much more. But it's not a Marketing book.

I'm talking about Thinking in Systems: A Primer, written by Donella H. Meadows and edited by Diana Wright - "a concise and crucial book offering insight for problem-solving on scales ranging from the personal to the global."

Thinking in Systems isn't Meadow's only book, but it's undoubtedly the most popular. Unfortunately, it was published posthumously, seven years after her death to cerebral meningitis at 59.

“Dana Meadows was one of the smartest people I ever knew, able to figure out the sensible answer to almost any problem. This book explains how she thought, and hence is of immense value to those of us who often wonder what she’d make of some new problem. A classic.”

You can find plenty of high-profile reviewers online, like this sample from Lester Brown, the Founder and President of the Earth Policy Institute.

First, what is a System?

To understand system thinking, we need to start by defining a system. Meadows provides us with the following description:

“A system is a set of things—people, cells, molecules, or whatever—interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time.” – Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems

It might seem strange to imply that everything is a system, but the author explains, "A school is a system. So is a city, and a factory, and a corporation, and a national economy. An animal is a system. A tree is a system, and a forest is a larger system that encompasses subsystems of trees and animals. The earth is a system. So is a solar system; so is a galaxy. Systems can be embedded in systems, which are embedded in yet other systems."

Systems thinking, then, is all about recognizing that everything is a system and that by understanding how systems work, we can better interact with and control the world around us.

Let's take a look at a few of the critical concepts of systems thinking.

Change takes time

Systems have stocks and flows. A simple example is a bathtub. There is a stock of water inside it, and three flows: the tap, the drain, and the overflow.

When you turn the tap on, the water starts pouring immediately, but it takes a while for the tub to fill up, even if we have the water running at full blast. In systems, it takes time for input changes to produce an outcome, and many factors can act as delays, buffers, and sources of momentum.

Similarly, depleting the stock of water requires opening the drain and waiting a certain amount of time.

Feedback loops keep the balance or reinforce change

Balancing feedback loops strive to keep the stock at a given value or range of values. If the value changes in one direction, the feedback loop will pull it in the other.

Think of a hot shower. You have two independent input controls for the flows of cold and hot water. With that, you can change the amount and the temperature of the running water. Your body is the sensor that provides the feedback necessary to choose the next course of action.

A fast and robust feedback loop can keep a system in balance, while a slow and weak one might struggle.

Regulating the shower temperature can be a simple task if adjusting the faucets causes the change in temperature in a short amount of time. The longer the feedback delay, the harder it is to get the output right, sometimes leading to painful trial and error experiments.

Reinforcing feedback loops lead the stock to grow or to decline. In this case, the change in stock fuels more change in the same direction.

Creating a reinforcing loop for users or revenue is the holy grail of startups pursuing exponential growth.

Expect the unexpected

Meadows claims that "Self-organizing, nonlinear feedback systems are inherently unpredictable. They aren't controllable." The problem is that we often struggle to visualize the nonlinear, purely because of how our brains are wired.

Meadows argues that we need to let go of control if we want to be systems thinkers, comparing the process to dancing. She writes, "In the end, it seems that mastery has less to do with pushing leverage points than it does with strategically, profoundly, madly letting go and dancing with the system."

The best dancers can let go of control while still moving gracefully. It requires a fluid approach rather than a rigid set of steps. To be systems thinkers, we need to be freestyle dancers instead of working through the YMCA.

So what can we learn from this? Complex systems are almost always more intricate than we estimate. We need to factor that uncertainty into our forecasting and decision-making.

This concept is self-evident when we look at the world around us. The more complex a project is, the more likely it is to go over budget or lead to unforeseen complications and delays.

Systems require purpose

Throughout her book, Meadows repeatedly urges readers to ask a simple question: "What's the purpose of this system?" According to her, systems consist of elements, interconnections, and a purpose. We tend to place too much emphasis on the first two and forget about the purpose.

"There are no separate systems. The world is a continuum. Where to draw a boundary around a system depends on the purpose of the discussion." – Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems

Even when we do remember to consider the purpose of a system, it often turns out that we were wrong. Meadows says that the only way to truly understand the purpose of a system is to observe it and see how it's working in practice. She explains, "Watching what really happens, instead of listening to people's theories of what happens, can explode many careless, casual hypotheses."

Systems Thinking in Marketing

If you've spent any amount of time in a marketing role, you've probably seen or built a marketing funnel. The funnel is a straightforward system with one input at the top (leads) and a linear downward path ending with paying customers. If only the world were that simple.

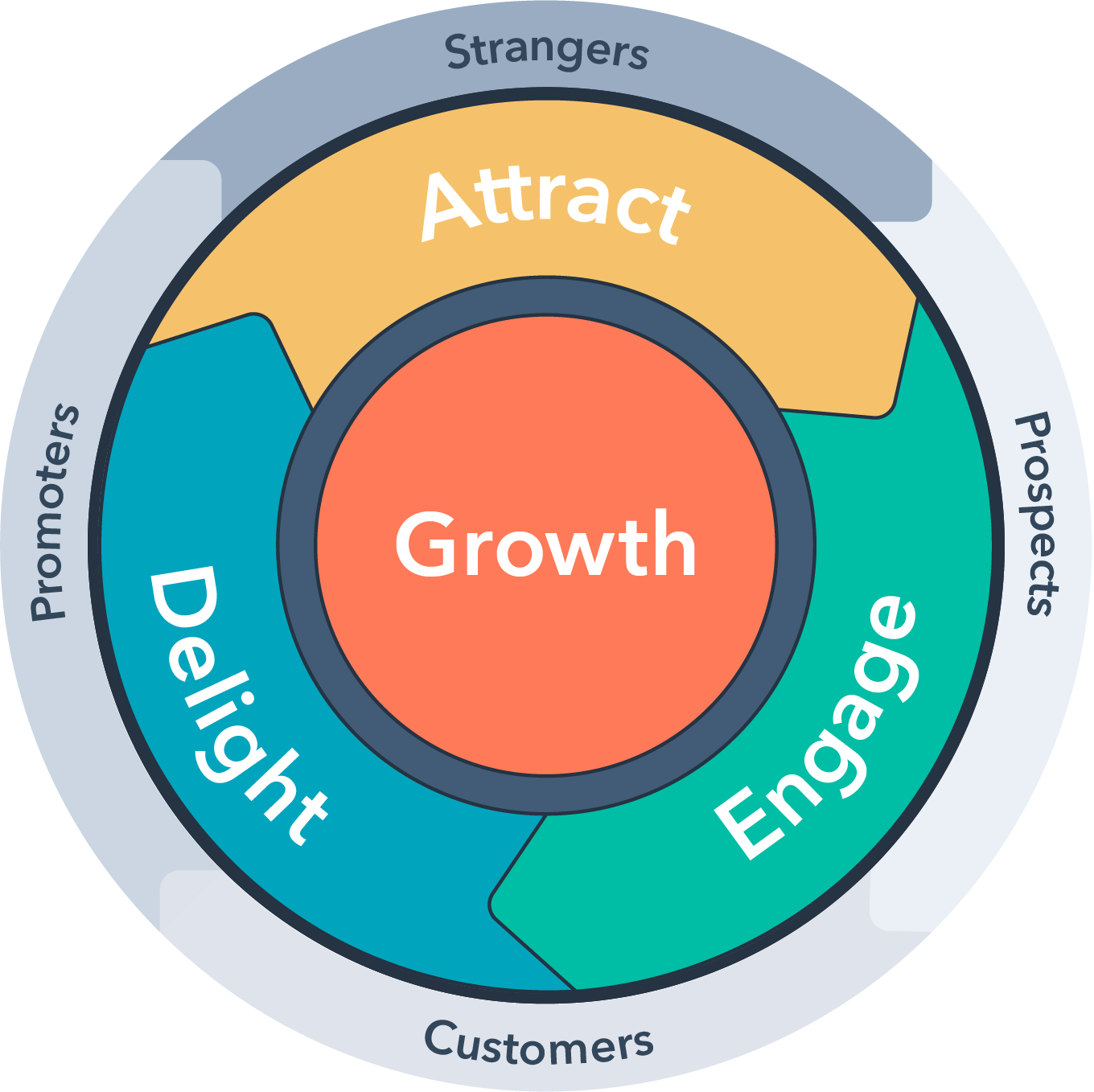

The traditional Marketing & Sales funnel is increasingly under attack, for good reasons. Instead of approaching customer acquisition as a funnel, a popular alternative is to model it as a flywheel.

A conventional mechanical flywheel stores energy to increase the overall momentum of a machine. You might have seen them in trains, buses, and cars. The idea of a marketing flywheel is to do the same thing by attracting, engaging, and delighting customers.

The heart of the flywheel model is growth. The rotation is caused by applying force and removing friction at each stage of the customer journey. The idea is to use that energy to drive the business forwards. The bigger it is, and the more power you apply to it, the faster the business will grow.

Friction slows down flywheels, and the same is true of the marketing flywheel. That means that savvy marketers who adopt systems thinking will look for these friction points and try to find ways to reduce them or to remove them from the equation entirely.

"Everything we think we know about the world is a model. Our models have a strong congruence with the world, [but] fall far short of representing the real world fully." – Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems

Thinking in Systems is one of those books that I recommend to anyone, no matter their profession or industry. I've only touched the surface in this article. There's a lot to learn from Meadows, and there are myriad different ways in which we can apply her lessons to the world around us.

For more reading recommendations, check out my reading bot.